Allusion is not Illusion

You'll pry my books off my cold, dead body. By the time you shift them all I'll be flat and dessicated.

Currently reading

Nearing the end of their lives, an elderly couple decides to bring up the question they have always avoided: How did you kill Gerry?

Yes, the same question from both Paul and Lucy. Turns out they have each spent decades believing the other to be responsible. But if it wasn't either of them, then...?

I thought this was a very interesting hook, and Dickinson's writing really pulled me in. However, there is a LOT of lead-up before we get anywhere near the meat of the mystery, and although it was nicely complicated I quickly grew tired of the narrators' voices and if the long series of meaningless affairs engaged in by the main characters and their sisters (I think inspired by the Mitfords) and friends. That's not moral prudery, I just found it uninteresting as a spectator to hear about the joyless personal lives of a bunch of unlikable people having it off with other unlikable people, who mostly don't even appear to like one another or be having any fun. Why they bothered beat me.

Still, a smart book, different from the run-of-the-mill mystery. I'll have a look at his other novels and see if any of them look more to my taste.

6

6

B is for Boring

I assume that this is intended to be used in an educational setting, perhaps to prepare children for their first trip to the library. Sadly, it is probably true that many children won't be taken early on by their parents and will go for the first time during elementary school. Certainly this book doesn't seem likely to inspire any child to go on his or her own. Both the art and the text are pretty boring -- and I speak as someone who loves libraries, books, and factual information.

First off, I think it was a mistake to format this as an ABC book. The constraints of the alphabet result in some important topics being skipped while other almost random items are inserted to fulfill necessary letters. Y is for Yellow: A ruby red rose or a bright blue sky/ show us colors so lovely to see./ But yellow's the color librarians love,/ 'cause they wear it to get their degree. Is that really important for small children to know? It's not like librarians wear yellow sashes to make themselves identifiable to the public.

That's not even the least relevant entry. Zestful? Really? And although Quest is a good word it is misleading, I think, to describe a quest as "a special search to find something important" and then have all the examples be about genealogical research (I'm guessing that's a pet interest of the author's).

Also, let me throw tact to the wind and state that these verses suck ass. I'm no poet and I could write a better-metered stanza when I was 9. The art work is more competent but similarly blah.

I did like the idea of having two texts for children at different reading levels. There is one bad four-line verse per letter, like the one above, and then side bars with considerably more information. The information was interesting in and of itself, although the dull writing made it a chore rather than a pleasure to read.

Instead of reading this book, kids, just look "Online" for information about libraries near you. "Online", in case you don't know, "is a new word that you'll want to learn." It takes quotation marks around it, apparently.

The tone of the whole thing reminded me cringe-inducingly of that fake-excited, talking-down voice that some educators use with kids to try to make them interested. Your library opens a door to the world,/ to the wonders of earth, sea, and sky./ And your Library Card is the key to that door./ When you use it, get ready to fly!

6

6

Kenzi Miyazawa died in 1933 of tuberculosis. Only 37, he was known only slightly as writer in his lifetime, primarily for his stories for children (in fact, this is how I myself first encountered him, with Night of the Milky Way Railway). Today he is considered one of the greatest Japanese poets of his generation, although, unusually, his recognition came through media and popular attention rather than the Bundan literary establishment.

A devout Nichiren Buddhist, Miyazawa almost entirely avoids the sexual and romantic themes that were prevalent in the poetry of the time. His writing is centered on the natural world, using nature themes even when discussing social and political ideas.

Politicians

They're just a bunch of scaremongers

Raising alarm wherever they can

And drinking their fill all the while

fern fronds and clouds

the world is that cold and dark

But before they know it

These fellows

Rot all on their own

Are washed away by the rains all on their own

Leaving nothing but silent blue ferms

The some lucid geologist will come along and put this on record

As the Carboniferous Age of man

His posture in the cover photo by Oshiima Hiroshi seems to have been characteristic, which makes sense given how many poems are about him walking outside and thinking.

Another significant influence on his writing was the early (age 24) death of his favorite sister, Toshi, also from tuberculosis. Miyazawa wrote several poems about her death, and also some in which her voice speaks to him from the woods. This one is one of his best known, after the titular poem.

THE MORNING OF LAST FAREWELL

O my little sister

Who will travel far on this day

It is sleeting outside and strangely light

(fetch me the rainlike snow)

The sleet sloshing down

Out of pale red clouds cruel and gloomy

(fetch me the rainlike snow)

I shot out into the midst of this black sleet

A bent bullet

To gather the rainlike snow for you to eat

In two chipped ceramic bowls

Decorated with blue watersheds

(fetch me the rainlike snow)

The sleet sloshes down, sinking

Out of sombre clouds the color of bismuth

O Toshiko

You asked me for a bowl

Of this refreshing snow

When you were on the point of death

To brighten my life for ever

Thank you my brave little sister

I too will not waver from my path

(fetch me the rainlike snow)

You made your request to me

Amidst gasping and the intensest fever

For the last bowl of snow given off

By the world of the sky called the atmosphere the galaxy and sun

The sleet, desolate, collects

On two large fragments of granite blocks

I will stand precariously on them

And fetch the large morsels of food

for ma sweet and tender sister

Off this lustrous pine branch

Covered with transparent cold droplets

Holding the purewhite dual properties of water and snow

Now today you will part for ever

With the deep blue pattern on these bowls

So familiar to us as we grew up together

(I go as I go by myself)

You are truly bidding farewell on this day

O my brave little sister

Burning pale white and gentle

In the dark screens and mosquito net

Of your stifling sickroom

This snow is so white everywhere

No matter where you take it from

This exquisite snow has come

From such a terrifying and disarranged sky

(when I am born again

I will be born to suffer

Not only on my own account)

I now will pray with all my heart

That the snow you will eat from these two bowls

Will be transformed into heaven's ice-cream

And be offered to you and everyone as material that will be holy

On this wish I stake my very happiness.

I happened across a German translation of this poem (I'm guessing translated from the English above rather than the Japanese) by Anja Greeb, so I'm adding it for any readers who prefer that language.

(view spoiler)

Since I know hardly any Japanese and haven't heard the poem read aloud (Hey, wouldn't it be a great idea to package translated poetry volumes with recordings of the poems read in the original language? Do publishers ever do that?) I can't address how accurate the translations are. I would guess that the sound is pretty dissimilar and that Pulvers was going for meaning.

Here is a painting inspired by his poems:

"The Forest" by Yuji Kobayashi, 2011

The titular poem "Strong in the Rain" comes last in this collection, so I will end my review with it.

Strong in the rain

Strong in the wind

Strong against the summer heat and snow

He is healthy and robust

Free from desire

He never loses his temper

Nor the quiet smile on his lips

He eats four go of unpolished rice

Miso and a few vegetables a day

He does not consider himself

In whatever occurs . . . his understanding

Comes from observation and experience

And he never loses sight of things

He lives in a little thatched-roof hut

In a field in the shadows of a pine tree grove

If there is a sick child in the east

He goes there to nurse the child

If there's a tired mother in the west

He goes to her and carries her sheaves

If someone is near death in the south

He goes and says, "Don't be afraid"

If there are strife and lawsuits in the north

He demands that the people put an end to their pettiness

He weeps at the time of drought

He plods about at a loss during the cold summer

Everyone calls him Blockhead

No one sings his praises

Or takes him to heart . . .

That is the kind of person

I want to be

7

7

Not feeling the enchantment

This was published a while ago, but still Millhauser was older than most of the characters he creates, and it shows in the point of view, particularly in regards to all the young women. They think like old women gazing back nostalgically at the wilder days, more romantic nights of their youths (and forgetting the angst and heartbreak that accompanied them).

Oh god, she's having wild thoughts, dream thoughts under the summer moon . She can feel the night working through her, she is a daughter of the night and the moon and her hair is streaming in the branches of the trees and her breath is the night sky.

I am not as young as Janet, but closer than the author is, and I can tell you no one thinks like this when they are twenty and making out with a hot guy in a thicket. Likewise I don't think most teen boys sit around thinking abstractly about how they would feel grateful and deeply moved if any girl let them have a feel.

Perhaps the his tone of elderly backward-looking is deliberate and I am missing the point of why it is employed, but it contrasts oddly with the sense of immediacy that the descriptions otherwise arouse, the restless young people and the dissatisfied loners (loners are all dissatisfied and lacking here, there is no possibility that one might be happy alone) wandering out into the night looking for -- what? Called by something, the moon stirring their blood, the panpipes which only the children hear.

I thought that was one of the weakest sections, by the way, the kids all at once going out to play in the dark and meeting Pan. It was so brief, nothing was done with it, even less than the moving toys section. And the mannequin... In fact, I think the book might have been better without any of the whimsical supernatural elements. The pervs and drunks and eccentric old ladies felt a lot more real than Columbine and that fucking twee unloved teddy bear.

However, I did in many places think the prose was very fine, especially when Millhauser is not trying to talk from anyone's point of view. He definitely has a strong rhythmic quality. My favorite sections were the recurring Chorus of Night Voices, which are strongly allusive of classical literature.

Hail, goddess, bright one, shining one: release him from confusion. Lighten his burden, banish his darkness: teach the sleeping heart to wake. Hail, goddess, night-enchantress: show the lost one the way.

I might try Millhauser again. I might not. I'm not very interested in reading fiction without characters. Anyone have a recommendation of a book of his that has character development?

6

6

Most insipid story I've ever read.

Okay, maybe some other Victoria moral literature I've read is equally insipid, but with more plot tension. This story really has no point, other than the obvious "You should be a dutiful young relative and live with grandmother and brighten her declining years, even if she was fine without you and didn't know you existed and vice versa."

Kate is a young woman has been orphaned. Since women don't live alone even if they have plenty of money (which she does; this is in no way a hard-luck story) she must pick one of her four uncles' families to live with. They all seem perfectly nice and are willing to have her. She goes to meet her grandmother and decides to live with her instead, because Duty. No one objects.

Okay, so what? There is just no conflict here. There is a slight implication that the uncles are too worldly and not dutiful enough, but Alcott says that they all offered to have their mother live with them and support her, and she refused. She has a nice house and a servant. She's lonely but, I'll repeat, declines to visit her children ever. I'm not exactly overwhelmed with pity here.

Kate arranges for the sons and their kids to come for Christmas. There is a pleasant gathering and everyone has a nice time. The End.

Yawn.

A temporal anomaly causes many Marvel mutants to be born hundreds of years earlier (so they are actually inhabitants of the Elizabethan era, not time-travellers). They must save the world (natch) despite the Inquisition, political intrigues, and supervillains.

The suppositions "Church = bad, Queen Elizabeth = good and enlightened" kind of annoyed me with their lame ahistoricism (suuuure Eliz I was against torture) but overall the setting was well done and interesting.

A Few Absurdities

Kharms' [Daniil Ivanovich Yuvachov,1905-1942] stories are very short. 'Garrulity is the mother of mediocrity,' he wrote in his diary. He also wrote, at the height of the purges that would eventually take his life (he died of starvation while in prison), 'I am interested only in 'nonsense'; only in that which makes no practical sense. I am interested in life only in its absurd manifestation.'

He had other pseudonyms as well. He wrote for adults and for children, stories, plays, poetry, erotica. Most of his adult writing, saved after his arrest by his friend, the philosopher Yakov Semyonovich Druskin, was not published in Russia until the Gorbachev period.

In this book we have a few brief stories, purportedly for children although adults might like them just as well. The first is "Mysterious Case," which is presented as an introduction, the writer directly addressing the audience. I'll reproduce some of it:

"This is incredible! Who can tell me what's going on? I've been lying on a couch for three days now, scared to death. I don't understand it at all.

It happened like this.

In my room, on the wall, is a picture of my friend Karl Ivanovitch Shusterling.

Three days ago, when I was cleaning my room, I took the picture down, dusted it, and put it up again. Then I stepped back to see from a distance if it was hanging crooked. But when I looked my feet turned cold and my hair stood straight up on my head.

Instead of Karl Ivanovitch Shusterling, a terrifying stranger was looking at me from the wall--

...I have taken a photograph of this picture and sent to the people who are making the book. They tell me that the kids who will be reading it are very smart.

Maybe you can tell me where my dear friend Karl Ivanovitch Shusterling has gone?"

A short bio and extensive sample of his writing is available here: http://lib.ru/HARMS/xarms_engl.txt.

6

6

I picked up this ridiculous-sounding manga about a silly girl who goes to a boarding school where students can bring their cats because I enjoyed the author's much darker King of Thorn series. I would never have guessed reading in a void that it was the same author; the only thing remotely similar is the fairly creepy mutated-looking monsters.

Here even the monsters are less serious. The threat is real but they're a tad silly so far: the giant rampaging anger hog and the fox-creature (it is called a fox but I wouldn't have guessed from the appearance) obsessed with hair. There is a so-far slight but interesting back story with some bad magic that happened in the previous century and the school being set up on the spot to guard against the return of the animal monsters. Otherwise it is pretty fluffy: the heroine Yumi is a kindly nitwit and none of the other students stand out much yet. My favorite character so far is the heroine's cat. Kansuke is grumpy but devoted to the dumb girl who rescued him from the street, despite her endless attempts to put him in silly costumes.

7

7

Yet another blog-to-book product. Like most of these, it was probably better as a blog (although I have not checked out the blog, I admit); the interest of the items wears thin after a few in a row.

Surprisingly, I found the text more interesting than than the maps themselves, most of which were neither that "strange" (strange may here be used in the new, meaningless click-baity way that words such as "amaze," "shock" etc seem to be on the internet) or that visually interesting.

Mm, okay, you could describe that shape as a "blue banana." If it makes you happy. Fine by me. Oops, I mean AMAZING!

Not really. But Jacobs provides pretty cogent explanations for the historical and political developments reflected in the maps, and I appreciate the research that went into that, even if sometimes there is needless verbal emphasis on how "weird" or "surprising" the information is.

Whether the text will be surprising or even interesting depends a lot on how much you already know. If you're an ignoramus forward-thinking modern person who doesn't realize, for instance, that the borders of nations were not always and eternally where they are today or that some countries are not monolingual, read this and get informed! Painlessly! If, on the other hand, you tend to give yourself headaches by trying to politely suppress your eye-rolling at the political and historical ignorance of the average person, skip this book. The funniest bits will end up on facebook and you can catch them then.

9

9

Arguing that the “Intellectual” emerged in France in the years just prior to the Dreyfus Affair, Datta sets her study two goals: “to separate the origins of the intellectual in France from the strict confines of the Dreyfus Affair and to examine the key role played by the literary avant-garde in the emergence of this figure.” She then proposes to demonstrate that the intellectual (whom she defines as a person “involved in public affairs” who possesses an “authority to speak... derived from their cultural and intellectual titles as well as personal fame”) from is born from the clash of traditional and avant-garde ideologies over national identity.

Intellectuals, in this study, are a fairly specific group, connected by bonds of age, schooling, and family. They defined themselves against earlier generations and by their scorn for the bourgeois values of the Third Republic. Datta relies heavily on the literary journals produced by this group, quoting from the writings of various individuals as she discusses the key intellectuals of the generation.

Next Datta discusses the groups' shared ideas, especially in regards to art and politics. The main source here is the enquete, which mystifyingly she does not describe. They appear to be a sort of opinion poll. She concludes that intellectuals agreed that they ought to be involved in the public realm but “to transcend divisions of class and rise above political parties.” However, they did not favor the new state educational system and rejected the attempts of men of lesser origins (including Jews) to join their elite. They saw themselves as belonging to both a class and a vocation.

Datta finishes with somewhat less original (i.e. drawn from extant scholarship rather than her own research) discussions of contemporary debates over the new woman and manliness, and individual versus national identities.

4

4

Allons en France! There we will learn useful French phrases to employ in common situations such as passing through customs, obtaining a hotel room, being trampled by the Republican Guard, sight-seeing, etc. A few travel suggestions, such as the use of the mosquito net to keep off dragons, may be outdated, but this is offset by Joslin's salutary inclusion of phrases which first-time travelers may otherwise neglect, such as how to decline a heaping bowl of spinach for breakfast or what to say when conversing with a statue of Napoleon. Also included are quotidian necessities such as J'ai vraiment besoin d'un glace (I greatly desire an ice cream), J'aime beaucoup lire (I love to read) and Mon chapeau est mouille (my hat is wet). Don't honeymoon by boat to a French illustrators conference in the 1950s without it!

Carroll argues that French fascism's foundations were laid before the Great War by nationalist writers who denounced the politics of the Third Republic and called for an “aestheticization” of politics.

French fascism is therefore of internal origin and not due to Italian or German influence. He views fascism as growing from fin-de-siecle nationalism taking a form that was primarily literary and characterized by an anti-semitism that was aesthetic and cultural rather than racial or biological, belief in a unified "National Will" that was organic to France, and a desire to apply literary aesthetics to politics.

Maurice Barrès became a Figure with the publication of his 1888 Cult of the Self (Le Culte Du Moi) and quickly parlayed his new popularity into an election to the Chamber of Deputies in 1889 as a Boulangist (making, I feel, Carroll's characterization of him as an intellectual a trifle disingenuous). He became Barrès close to Charles Maurras, founder of Action Française, who dreamed of rebuilding a Royalist France with strong cultural connections to classical Greece, which for him represented ideals of order and beauty. He viewed German and Jewish ideas as threats and rejected democracy on the grounds that it was disordered and without beauty. "France should be defended because France is beautiful," Maurras argued.

Barrès likewise saw his nation as unique, defined by culture while others, in his view, were defined by race. French culture was rooted in "land and the dead" and constituted a national self that must be always on guard against contamination by foreign influences.

Carroll's third figure, Charles Péguy, was on the contrary a passionate supporter of the republic -- or at least of an idealized republic that would exist once the "Republican race" had, again, gotten rid of those foreign contaminations. Then politics could be remade in the image of art. For Peguy race was derivative of culture, shared experience, and religion. Republican mysticism was incompatible with "Oriental Judaism." Despite being a prominent Dreyfusard, Peguy believed that the Jewish population would always remain separate from the body of France.

These three figures advocated totalizing, if not totalitarian, politics, and produced texts which created intellectual foundations for political and literary fascism. Unfortunately, Carroll never explains more precisely or pragmatically what sort of fascism he has in mind or how these ideas may have later been actualized.

7

7

I read this in translation,

so I can't say for certain

maybe there is some metric by which it is poetry.

Maybe the lines are not merely

broken because Sebald felt like it.

Perhaps in German this is not prosaic --

by which I am not calling Sebald's writing

by any means quotidian but

I saw no reason it could not be

arranged in full text lines.

It would sound just the same,

it would be easier to follow,

it would save space and the lives of trees.

Did the trees do something to you,

morbid walker of Suffolk,

moor-mournful Sebaldus?

I like your prose, I do.

The Rings of Saturn was great.

This is like Rings watered down.

It even covers several of the same

subjects (Suffolk, sadness, Edward Fitzgerald)

and reads much the same, half

travel guide half thought-piece.

But less. Less than Saturn.

And I want more.

Line breaks are not more.

I

Matthias Grünewald

last great medieval artist,

rejector of Renaissance classicism.

Married to a convert Jew,

although Sebald insists the man

was gay for Neithart.

II

No portrait is known to exist of

Georg Wilhelm Steller

botanist, zoologist, physician, explorer,

drawer of this sea-cow.

Named after him, the species outlived

him by only twenty-five years.

Except his Jay all other

creatures named for him are now

extinct or in danger of it.

III

W.G. is not a bit hubristic

to include yourself among these greats?

Well, let it slide.

The past is another country,

and anyway,

the man is dead.

7

7

Werner Herzog is walking, walking, walking. He is walking to Paris because of magical thinking. His friend Lotte Eisner cannot die before he arrives. He drinks milk and eats tangerines and breaks into empty vacation homes at night. He finishes someone's crossword puzzle, he urinates in someone's boot. He sees things, he describes them. He describes things he probably does not see. I'm pretty sure some of those things could not have happened, it is not always easy to tell what is real and what is in his mind. I feel justified in these comma splices because Werner Herzog loves commas splices, they are everywhere. Werner Herzog and I both think in comma splices, and we've both read Where's Waldo?, these things make me feel more sympathetic to him even though he appears to be insane and demonstrates extremely poor judgment.

My only regret is that this book did not include photographs. Damn that Frenchman who refused to sell Werner Herzog film!

7

7

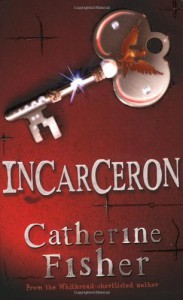

I found the setting, the idea of the book, more interesting than the characters and action. And yes, I do mean that the setting is the idea. Incarceron is an unfathomably huge prison, self-sustaining and completely cut off from outside contact. Built centuries before the unspecified future age in which the story takes place, it was meant to be a utopia where prisoners were rehabilitated and formed their own communities, never returning to the rest of society. But the prison itself is aware and seems not to care about reform the "criminals," who at the point of the story are generations removed from those condemned and hardly believe there is an outside. Their lives are meager and desperate, surviving by theft and violence in an environment of increasingly scarce resources. The world they left behind is hardly in better shape, thanks to decrees that emulate the world of early modern Europe and forbid progress or social advancement. The majority of people are poor and illiterate, fearfully serving a tiny elite who scheme constantly, trapped in an empty and stagnant system.

In the prison we begin with Finn, a boy with no memories who survives by joining a band of thugs and helping them rob and enslave others. He and his oathbrother Keiro take a strange crystal from a woman they capture. It allows Finn to communicate with Claudia, a girl in the outside world who is the daughter of the prison's Warden. Aside from Finn and Claudia I didn't feel the characters were developed adequately, especially the villains. This was especially noticeable to me as I recently read Fisher's Darkhenge, which focuses much more on emotional and domestic concerns; one might say it examines a microcosm whereas Incarceron invents a macrocosm.

I was a little annoyed by the extreme cliffhanger ending, as I didn't really like this so much that I want to read the sequel.

Over a decade after its highly lauded publication I still have not entirely made up my mind as to how I feel about this book. On the one hand, it is intelligent, interesting, and for the most part well-researched. On the other hand, there are some pretty significant errors and omissions.

To begin with the most glaring: Rodgers' underlying chronological supposition concerning transatlantic communication is mistaken. He asks how and why a transatlantic intellectual discourse grew up towards the end of the 19th century, and answers this question with the growth of progressivism, relating the “new” discourse to the social and political changes of the 1890s.

In fact, transatlantic intellectual discourse had been solidly in place well before the period of Rodgers study. Anyone who has studied 19th-century intellectual life could have pointed this out to Rodgers, whose area of specialization is the 1920s. Presumably neither he nor the publisher sought feedback in this area, which is a great pity.

However, if your area of interest is progressive movement after the First World War, its ideas and influences, and the root causes are less important to you, Rodgers' analysis of these elements is useful and intelligent. It is also perhaps timely, as Rodgers' sees American progressives as looking to Europe for ideas and models in a period of “rapid intensification of market relations... and the rising working-class resentments” (59).

Interestingly, one of Rodgers contentions is that a difficulty faced by American progressives was not in finding models in the first place, but in finding many and having to choose between them. They wanted, to put it very generally, to find a path of moderation between the “rocks of cutthroat economic individualism and the shoals of the all-coercive statism” in time to prevent the rise of working class socialism. The debate in these circles included labor regulation (minimum wage, maximum hours, et al), urban planning, and social insurance.

After WWI, in contrast, the exchange of ideas between Europe and the US became more even, especially after the New Deal, which many progressives viewed as the gathering up and culmination of ideas from both sides of the Atlantic. Rodgers argues convincingly that this period and its ideas and political actions were of lasting influence in the US and many European nations.

Even for those interested in the late 19th century there is material of value here, although it less original in its research. Rodgers discusses sociological tourism (largely but not uniquely American), using the most famous example of Jane Addams multiple visits to Toynbee Hall and W.E.B. Dubois' study of German Kathedersozialisten. He returns to this theme in the 1930s with the Lewis Mumford and Catherine Bauer's investigation of housing reform and modern architecture in Germany and Austria. There are also excellent, if not precisely stimulating, examinations of experimental reform attempts in the area of mapping, railway ownership, agrarian reform, mortgages, and, probably best known of these, the Farm Loan Act of 1916.

Other chapter topics: the Paris Exhibition of 1900 and its Musee Social, American students in Germany, municipalization (i.e. the contests over civic versus private ownership of utilities), “war collectivism,” agrarian cooperatives, rural reconstruction, and William Beveridge's plans for postwar reconstruction in Britain. That's just an overview; we also get sanitary improvements, slum clearance, public baths, urban gardening, pensions, health insurance, the role of unofficial* policy advisers, mutual benefit societies – all of which, of course, varied greatly from one place to another.

*Oddly, Rodgers doesn't make much mention of official ones, i.e. those who actually employed by the government or universities to study these questions. It is all philanthropists and philosophers for him. People like Edgar Sydenstricker, Milbourn Lincoln Wilson, and Lewis Cecil Gray don't figure into his chart, although they were essential providers of communication and sponsorship.

Another odd omission is the issue of American nativism. Many historians, such as Harry Marks, would argue that this was a major factor in the failure of Progressivism in the 1920s. I expect legal historians would also debate his minimalist reading of the role of the courts in this process.

There are far more books on this subject than I can list here, but a few suggestions for further reading:

The Emergence of the Welfare States

The State and Economic Knowledge: The American and British Experiences

Social Scientists And Farm Politics In The Age Of Roosevelt

States, Social Knowledge, And The Origins Of Modern Social Policies

Carroll Wright and Labor Reform: The Origin of Labor Statistics

Transnational History

British Social Reform and German Precedents: The Case of Social Insurance 1880-1914

Municipal Services and Employees in the Modern City: New Historic Approaches

7

7

2

2